Local author and professor Dr. Hall sat down to talk with us in anticipation of her appearance at the Coventry branch on Monday, March 18, at 7 p.m.

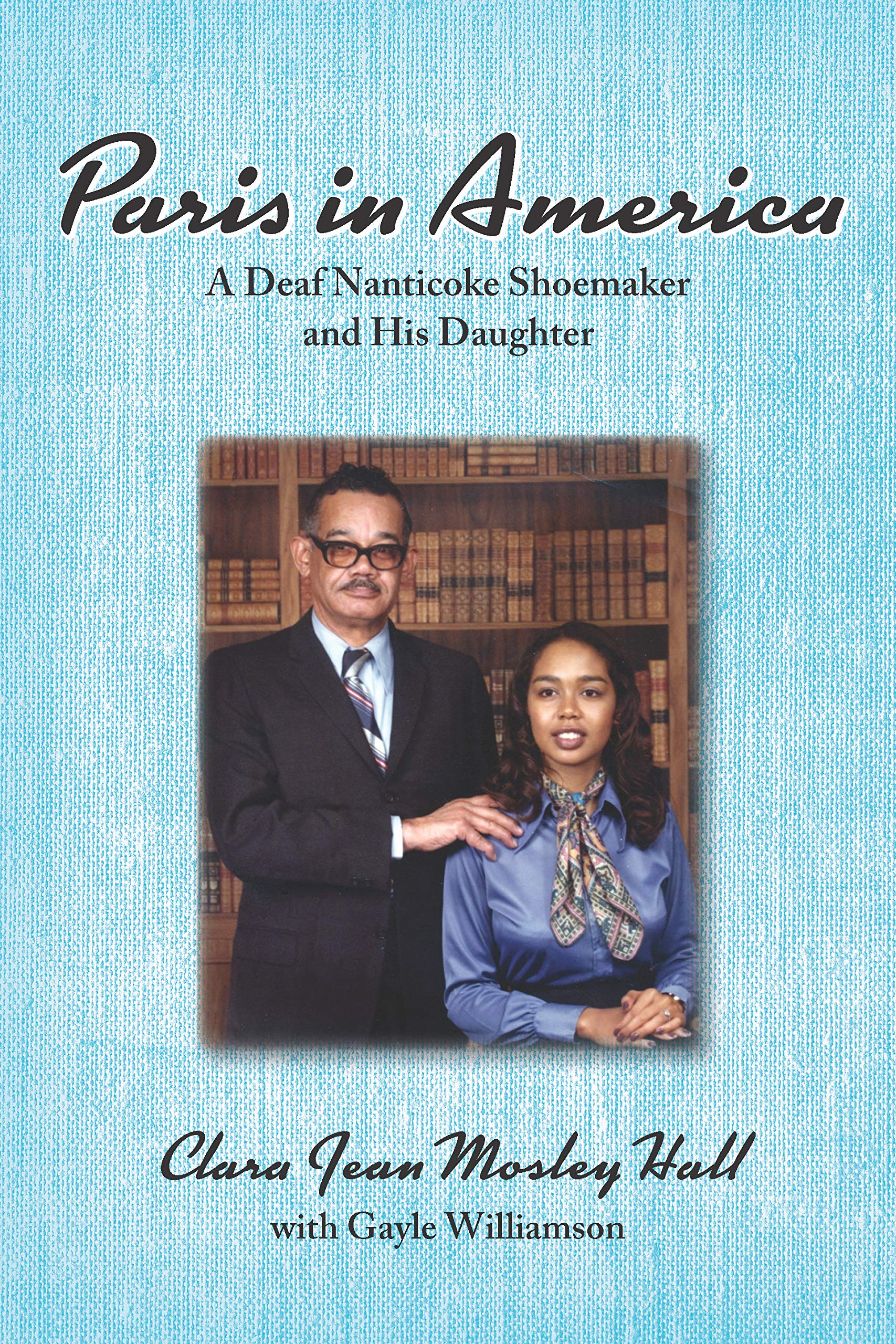

Dr. Hall’s first book is Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter. In this memoir/biography, Dr. Hall describes her many intersecting identities; Native American, African American, Deaf, and hearing, while sharing how she and her father overcame challenges which ultimately shaped her successes.

Q: What inspired you to write your new book, Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter? How would you describe it?

A: Somewhere along the line, I heard someone say, “Everybody has a story, and everybody should write it down”. It resonated with me because I have two daughters, and in my family no one has been able to trace their genealogy beyond their own parents. I was in the same boat – my daughters never knew my father because he died when my oldest daughter was a year old and the youngest one hadn’t even been born yet – so I thought I should write the stories I remember and give it to them. And as I got into it, I was thinking, “Wow, my father was such a wonderful man, he had a great work ethic.” I thought, “He would be a wonderful role model for other deaf students.” And as I got further into it, I discovered this book is great for everybody! Because I really feel that we are all one, and everybody has some sort of struggle, so I thought that the reader, whoever they might be, would be able to read our story, and see how we dealt with trials, and how we got to our triumphs. And I found that that was really our secret: that you don’t give up. If you have goals, you just keep going. And I thought, “Well, this book is for everybody!”

It’s a memoir, but it’s an autobiography/memoir because it’s about my dad’s life from when he was born to the end of his life. It’s a memoir because, for myself, it’s from when I was born to when he passed away. It’s a story of both of our lives: his, and then when I came along, his and mine, together.

Q: In your book, you write that Deaf Native Americans have many additional barriers when it comes to receiving equal access to communication with their own communities, often causing them to lose the ability to learn about their heritage. Did your father experience barriers accessing his Native American heritage, growing up Deaf? As a hearing individual, were you able to access spoken knowledge of that heritage that your father could not?

A: First of all, my father didn’t go to school until he was nine years old. Most of the students go when they are four or five, so he was behind most of the students. But, in terms of his native ancestry, it’s a little different than those Native Americans that live out in the west. Our particular tribe, East Coast Nanticoke Indians, stopped having their powwows and native activities in the 1930s, and they didn’t start again until the late 1970s. So, none of us actually were able to access our native history and ancestry. We knew that we were native because my aunt would take us down to visit people and relatives in the community, and we just knew that we looked a little different than everybody else, and we heard stories. Yes, we’re part native, but none of us had access to that information. So in that sense my father really wasn’t any different than myself or anybody else that could hear. It wasn’t his deafness that kept him from his heritage, it’s just that we weren’t doing any of those cultural activities that would allow us to know that history. So, I learned about it pretty much later in my life. I knew I was native, but we didn’t start going to the powwows till the 70s, 80s.

My youngest daughter, who attended Dartmouth College, which is known for supporting its native student population, became more interested [in our heritage] because she knew that she had that native background, but didn’t know much about it. She joined the group of native students there, and started learning how to dance. She would come home and show me, and because she was on the east coast, she would visit Delaware, which is where I’m from and where our tribe is, more often than I could get there, because living in Ohio, it’s a distance! So, she started going to the powwows by herself, and she said “Mom, you’ve got to come.” And it’s because of her that we now go every year, and I’ve now become one of the lady traditional dancers. So I really have to give her credit for sort of pulling us in, because she was interested. In fact, she is doing her dissertation on language revitalization of our tribe. We want to support her, so now we engage in all of those activities as well. We all do it as a family now.

Q: You grew up experiencing many cultural identities: African American, Native American, hearing, and Deaf, to name just a few. Describe what it was like for you to be the hearing daughter of a Deaf Native American father.

A: I think the deafness was the predominant culture and you have to understand too that it was the era that I grew up in. I was born in 1953, so it was before there was any professionalization of interpreters. The registry of interpreters for the deaf didn’t begin officially until 1964, so I lived during the era of deaf parents using their children to connect with the outside world. Today, we say that’s probably not a good thing to do, but back then, I was all he had and so it was a responsibility for me to interpret for him in situations that probably, today, for children, you would not want to expose them to, such as the divorce between him and my mother. I was maybe seven or eight at the most, and I just remember the lawyers using language that, for me, cognitively I wasn’t there yet. I didn’t have that kind of vocabulary, and I did the best I could.

There were doctor’s visits where, usually we go in and we have the understanding that everything is confidential, but here my father has to share things with his female daughter that was very young. So a lot of times I felt like I was the parent, because he relied on me for a lot. And I didn’t mind at the time, when we were together. I just recognized that it was what I needed to do to make sure that he was able to navigate the world the best he could.

Because I’m an only child, and because my mother, who was also Deaf, left when I was four, it was just he and I, and his sisters lived across the street and down the street, but they usually communicated with him through gesturing, or over-accentuating the mouth movements so he could read their lips. I was the only one that really picked up the language, so anything in detail or anything of depth fell to me. But they could say “come, dinner’s ready”, or something like that, but with anything substantial, they would have difficulty.

Q: Growing up, how did you and your father navigate and support one another’s respective identities and their associated gifts and challenges?

A: For him, he understood that I was a hearing child. And he always made sure that I had auditory input. He made sure that, in my room, I had my own TV and my own record player or radio, and we lived close to relatives. Delaware is small town-ish. People live across the street and down the street, so we come into each other’s lives on a daily basis. He made sure that I was immersed in the hearing culture, that I received auditory input. So, I never had some of the problems that other children of deaf parents have with speech. There are those stories where children grow up pretty isolated. You’d think that in a city that wouldn’t be the case, but you have more things, more activities, and more events that Deaf people can go to. So you can go to a Deaf church, you can work with Deaf people, and so those children of Deaf adults don’t necessarily get as much exposure as I would living in a small town, because my dad and his four other friends were the only [Deaf] ones. So I feel like he tried to support me as a hearing child and made sure that I had all the auditory input that I could receive. He supported that.

Q: How did your relationship evolve as you both grew older, witnessed shifts in segregation laws in Delaware, and expanded your worldviews?

A: As a young child, my father was everything. And he always was, throughout my life. But growing up, that was the height of Jim Crow Laws. And I talk a little about in my book, how we were not allowed to sit in the orchestra section of the theater and had to sit up in the balcony, but we always thought that was the best seat anyway! And today, I still go as far up in the balcony as I can go because I just think I can get a better perspective of the movie. But, after desegregation came to town, my father had a harder time understanding that because I would always tell him, “Dad, you can go in the store now, you can go here, you can do that”, and he would understand that, but before he would ever go in, he would always ask me, “Are you sure it’s okay?”, so I think it was a little bit more difficult for him to understand those changes.

And of course as I became a teenager I was like any other teenager. I became a little rebellious, and a little tired of having to be the interpreter for everything, and I got into boys, and at thirteen you think you know everything, and it was quite challenging for my dad. I was no longer the sweet little 5-year old. And the phone – I was always on the phone – he saw it as the enemy. So, he took the phone out, and we didn’t have a phone for a while. I had to use a neighbor’s phone to make calls or have people call me. But it was a typical teenager-parent relationship and it changed from when I was five.

But after I became more mature, I grew up, and our relationship changed again. I understood his situation better and I hopefully became a little more tolerant. It was difficult for both of us, because I just wanted to be a normal kid, and I started to see how other friends and their families interacted, and it was a little bit different for my dad and I. But on the other hand, I loved him so much and he loved me so much that I think that really got us through any challenges that we faced.

Q: When writing this book, was there anything that really surprised you as you researched and reflected on your father’s and your own life?

A: Well, not so much with my dad, because I was the only one that could communicate with him well, so he told me everything. So most of the stories that I remembered [about him] came from him. But I can tell you that the biggest surprise to me when I was writing the book and doing the research was not so much about my dad but about my aunt. It was his sister and she helped him raise me. My father was a staunch Democrat, and I found out that his sister was a staunch Republican! And I didn’t find that out until I was older, until I started doing this research, and stories came out about who she voted for. And I called her Mommom, and I’m like “Mommom, you voted for him?” and she was like “Yeah, I mean he was the Republican candidate”, and I was like “You are?” And I mean, to live with someone your whole life and not know that, that was the biggest surprise of all I think.

And then some of the stories that my other aunt, my aunt Grace, told me, I did not hear from my dad and it was kind of a surprising story. She was talking about how he hadn’t found out about the school for the Deaf yet, so he noticed that his sisters were leaving the house every day and they would put on nice clothing, and he was curious. Where are they going? So, he snuck out of the house and followed them, and he went to the school house and he saw all these children sitting in the room and there was this lady up at the front and he didn’t know who it was (and of course it’s the teacher). But he noticed that she would talk, and when she said things the students would all raise their hands. He didn’t know what that was about. So he sits in the back of the room and he gathers this information and he notices what they’re doing so he does the same thing. He raises his hand but he doesn’t have any idea what the teacher is actually asking, so all the kids turn around and look at him and they’re giggling. But he just wanted to see what it was all about and what was happening. But again, he didn’t go to school until he was nine so he had no language. They just communicated with him through pointing and gesturing. That was a cute little story that he had not told me.

Q: In addition to being a published writer, you are also a professor of American Sign Language and Interpretation at Tri-C, as well as a mentor and advocate for Deaf students from diverse backgrounds. What inspired you to take this path?

A: I have to give the credit to my husband, Dr. Howard Hall. He’s a psychologist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s UH Hospital. Everybody in his family had gone to college. Currently, everyone in his family has some sort of doctoral level degree, except maybe a couple of people and they have Masters. I was the first one in my family to go to college. So he came to Dover to go to Delaware State undergrad, and that’s how I met him. He asked me one day, “So where are you going to college?” And I said, “Well we don’t have money for that. Nobody in my family has every gone to college,” and he said, “Well you have to go to college!” And I said “How do you expect me to do that?” We had several conversations about that, but eventually he convinced me that you can do this.

What I found is that once you take that step in a particular direction, the universe does rise up to meet you where you are, and everything fell into place. So I went to college, and I was going to major in Business, and he said, “Well you have this skill. Why are you wasting it?” And I thought, “What skill? This is just what I do.” I didn’t really see it as a path to a career, working with Deaf people. So I did major in business at the undergraduate level at Delaware State in Dover, but then I went on to get my master’s in Deaf Education at Western Maryland College (it’s now called McDaniel College). After that, when we moved to Cleveland, the opportunity arose for me to get my PhD at Cleveland State in the Urban Education program, so I did that and then I did my dissertation looking at Deaf students in regular public schools and looking at the concept of racelessness. So it just kind of led me there because my husband said I should be going to college. I’m very grateful to him because it was the right decision. Sometimes you’re too close to what you do to really see it, but for him, he was from Cincinnati, and his family background being different, he was able to give a fresh pair of eyes to me and my family and was basically an inspiration for my life today.

Q: What do you hope your readers will take away from reading your book?

A: I think that we all face different challenges in life. Even though my challenges may be different from the reader’s challenges, nevertheless they’re challenges. People tend to see what my life is today. I had a girlfriend that said “Oh, your life is a fairy tale”, but they don’t recognize all of the trials that have gone on before. I want the reader to notice that yes, in the end I have a PhD, I’ve written a book, it’s doing well, I have a wonderful life, I have a great career, but I want them to also know from the beginning that there were challenges, and then there were successes, but then as soon as there was a success, there was another challenge! The ups and downs of life really are no different for any of us. I hope that they can see that if they have a dream, if they have a goal, if there’s something they want in life, they can have it! They just can’t let the trials and the challenges deter them. I have a quote in the book that says “You’ve to go through your own trials, on your own trail, to get to your triumphs”, but if you stay on that trail, don’t give up, keep your eye on the prize, you can get there. I am a testament to that. It does work.

Q: Talk a bit about your creative process. Do you have any advice for beginning or aspiring writers?

A: My creative process is kind of interesting. A lot of it was inspired. Once I decided that I needed to write this book for my daughters, I started to get this inspiration while I was in the shower. I don’t know if being in water is a facilitator of inspiration, but I would get these images in my head and thoughts about what to write about. And as soon as I would get out, I would go and write it on a piece of paper. A lot of my inspiration came from that, and once I actually sat down at the computer to write something, it would just flow. It’s almost like I didn’t write it. I feel like it comes from the creator, and it’s just coming through me. And then of course I had people to edit, and there was a lot of that. If I was lying down in bed and I’d think of something I’d jump up and write a note to myself so I would remember in the morning what I wanted to talk about. That was my process, and it may be different for other people, but I say whatever works for you, just do it!

I never saw myself as a writer, in fact, that’s why if you notice on the cover of the book, it says “With Gail Williamson”, who is a colleague of mine at Tri-C. I never felt confident as a writer. I had written my dissertation and I had actually published the basics of my dissertation in an article with the American Annals of the Deaf with Gallaudet University Press, and I just thought, I don’t have any experience with a popular audience. I don’t want to put people to sleep, and I want them to enjoy the story, so I elicited the help from my colleague.

That’s one thing I would say to people. A lot of people say they have this goal, I want to do this but I’m not good at that. You don’t have to be! If you just take a step, the universe will provide you with the people and the materials that you need, and for me, this person was in my life, and she said yes, she would help me. I would say, just take steps, take baby steps every single day. Think about it, what can you do, and once you think about what you can do, the rest will fall into place.

Q: Do you have any advice specifically for Deaf students who come from diverse backgrounds?

A: For deaf students who come from diverse backgrounds, my advice to them is that it really doesn’t matter what your circumstance is. I know that all of us have certain barriers in society that we face, whether it’s the color of your skin, or your gender, whether you’re gender fluid, or your religious beliefs. I would say, even though all of those are very different, they still represent challenges to you, but you have to overcome them. You have to realize that you are still a major part of the cosmic energy that flows through all of us, and that you are here. The reason why you are here is to contribute something. Everybody is special in some way. Everybody has something that they can contribute, and you should do that, because if you don’t, then the rest of the world loses out on what you could have brought to the table.

I think that because of the diversity, whether it be your race, your gender, your religion, whatever it may be, that allows you to have a specific perspective that someone else may not have, and if you contribute that, you can make the world a better place, no matter how small you feel that contribution is. This is the one book that I started out writing just for my daughters. I thought they would be the only ones to read it! But I’m finding that when I speak to people, they resonate with the story and it inspires them to do whatever it is, to search for their purpose in life, and to do it, to go about getting it done. So we all have a contribution to make. It doesn’t matter, just because we talk about diversity. Diversity means so many different things, but don’t let that stop you.

Q: Who are some of your writing influences? What are you reading right now?

A: I like books and writers who tell their truth. I’m not a big reader of novels. I like autobiographies. I like spiritual and inspirational pieces. I love Michael Bernard Beckwith’s Life Visioning. I like people like Gary Zukav, The Seat of the Soul. Right now, I’m reading The Wisdom of Sundays by Oprah Winfrey. My favorite television show of all time is “Super Soul Sunday”. I like the variety of people that she brings on the show, and they talk about their inspiration for whatever it is that they’re doing. I get inspiration from that. The Wisdom of Sundays is a collection of pieces of what they have said on the show, compiled in a book. It’s something that doesn’t go out of style, getting more of that inspirational input.

Q: You have an event coming up at our Coventry branch on March 18th. Can you tell me what you have planned for that?

A: I will be speaking about living at the intersection of cultures. When I started working on the talk, I came up with seven cultural intersections. There’s probably more, I’m sure, but I’ll be talking about the individual cultures – including Deaf and hearing, Native American, African American, and then combinations of those. Then I have some videos of things that I’d like to show the audience. There’s some pieces about Native American Sign Language that I have side by side with American Sign Language, so that people can see the difference between the two. And just sharing how I’ve integrated those cultures – some of the successes of integrating those cultures, and some of the faux-pas that I’ve experienced.

Sometimes you forget, because there are different ways of behaving in each of those cultures, and I do a lot of code switching, where you act one way in one culture, and then you transfer that to a different culture. Sometimes you don’t think about it and you just respond, you react, and sometimes those have not been very successful situations of code switching, and people kind of look at you strange, like “why did you do that?”, and it’s like “uh, sorry about that”. You just kind of apologize and move on, hopefully, and they understand. So I plan to talk a little about each of my cultures in the talk.

Q: Anything else you’d like our readers to know?

A: One thing I would like to add is that when I was younger, sitting at the kitchen table with my aunt and her husband, my Uncle Pick, they would talk a lot about this gentleman by the name of T. Boone Pickens. Now, it makes sense to me why they talked about him so much, because Mr. Pickens, I believe, is a Republican. And they were very impressed with him because Mr. Pickens was a wealthy business magnate. They heard stories of him that if people would write him a letter and say that they needed something, like a furnace or a new kitchen stove, that he would give them that. And that stuck with me, it really impressed me that someone could have so much money that they could take care of their own needs and then be able to also help other people. Because oftentimes, I was on the receiving end of that. My aunts used to go to the Salvation Army and bring back clothes for me. Today, it’s kind of cool, a lot of people do that on purpose but for us it was a necessity. This was a way to save money.

Mr. Pickens just impressed me, so as an adult I started a scholarship with the Cleveland Foundation in the name of my father. It’s the J. Paris Mosley Scholarship Foundation Fund, and it’s for Deaf students who want to go to college, have the ability to go to college, but need some financial support. I began that in 2000, and I have been able to support the college endeavors of about fifteen students now, and that is because of Mr. Pickens. As an adult I actually Googled and contacted him. I talked with his secretary, and explained to him that I was writing a book and I probably would be doing interviews, and I did plan to give him credit for why I started the scholarship fund. He was nice enough to write me back a nice little note saying that he appreciated my note to him and that he appreciated why I wanted to do the fund, and he was glad that I let him know that he was my inspiration for that.

For more information on Dr. Hall’s upcoming event at the Coventry branch on Monday, March 18, at 7 p.m., click here.

To check out Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter from our catalog, click here.

Finally, excerpts of this discussion were recently aired on Biblio Radio — click here to listen to the segment.