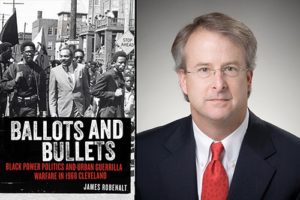

Local author and historian James Robenalt sat down to talk with us in anticipation of his appearance at the Coventry branch on Wednesday, November 7, at 7 p.m.

Robenalt’s most recent book is Ballots and Bullets: Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland. The book examines the causes and legacy of the July 1968 unrest in Cleveland’s Glenville neighborhood, where black nationalists—led by local activist Fred “Ahmed” Evans—and police engaged in a conflict that left 15 people wounded and six people dead, including three white police officers.

What inspired you to write this book?

There’s a secretary at my law firm whose father was shot and badly wounded during the shootout. She always told me about her father having been disabled working as a Cleveland policeman. In the summer of 2016 I said, “Tell me more about your dad.” She brought in this little book that had been done about the shootout, and as I was reading that book, the news came out that a black nationalist had gone to Dallas and ambushed and killed five white police officers at a Black Lives Matter event. That immediately brought to my mind the question, Why are we still here 50 years later? This incident was almost identical in terms of black grievances against police resulting in the taking up of arms and the ambushing of police. Why are we still here, 50 years later? That’s what I set out to answer in this book.

What surprised you the most when you were doing your research?

The FBI had been very active here in Cleveland surveilling black nationalists, and I was really surprised to learn how many people had been used in that operation. Ahmed Evans group–which was called the new Libyans—probably numbered at its height about 30 guys, and within that group there were about four or five FBI informants. I discovered those files in the national archives as part of researching this book, and it was a huge discovery because those files had just been declassified a couple years earlier. It showed that the FBI was hiring informants who ended up providing an almost hour-by-hour account of what happened, so I could write the book almost in real time with the FBI files. That was an amazing discovery for me.

Give us a brief synopsis of the events in the book.

1968 was a turning point. Cleveland had elected the first African American mayor of a major U.S. city in 1967, Carl Stokes. It’s hard to overstate the promise that people felt from that election, not just here but around the country. He was on the cover of Newsweek and Time, he was the Barack Obama of his day. He was a lawyer, he was charismatic, very dynamic—you talk to people about the day he was elected, and they mention the jubilation that people felt. Then, when MLK was killed, [Stokes] walked through the streets of Hough and kept the peace. So for a brief time everyone thought, Well, the experiment is working and we’re on a new path.

Unfortunately, the violence of that time and the unhappiness of the African American community, including Ahmed Evens and his black nationalists—the scars were too deep at that point. So, even though Evans is one of the guys that walks the streets that night with Carl Stokes the night that King is killed, he eventually turns bitter. Around that time Carl Stokes starts a memorial fund for MLK—the idea is jobs, healthcare, housing for the inner-city of Cleveland—and he calls it Cleveland Now, and within a month it morphs into a billion-dollar program. This is 1968 funds. Things were on the cusp of a new day in race relations and Carl Stokes was the leader who was going to prove it was possible to have black leadership that was successful in inner cities like Cleveland, which was very representative of most of the country.

But because of these scars and the destructive racism that had happened here in Cleveland and around the country, Evans, unbeknownst to Stokes, used money from Cleveland Now to buy rifles to shoot policemen. So that was the bitter end of the experiment and it really was the end of Carl stokes. He was re-elected, but he was fighting with the white establishment from that point forward, and with the police who were really angry that his money had been used to buy guns to shoot them. So rather than use taking three or four steps forward, we ended up taking about 20 steps back.

What is the legacy of these events?

On many fronts, there are important issues that remain from back then. It really changed Cleveland, it changed the nation, Richard Nixon was elected in part as a reaction to all this race violence, and he did away with the war on poverty and began the war on drugs and began incarcerating AA males in particular in large numbers—that’s what happened 50 years ago, and that’s why we have somebody in Dallas at a Black Lives Matter event – it’s all still churning through this destruction of racism. That’s the main thing that comes out of this book.

There are, also, a lot of other important stories of individuals on both sides—on the police side there were some heroic people, on the black nationalist side there were people who believed they were involved in a political war—those who were killed that day are considered to this day in that community to be martyrs to a cause. It’s a tragic story but it’s one that has been buried in Cleveland, purposefully. The Stokes wanted to forget about it because it really was the end of his mayor ship, the police wanted to forget about it—they didn’t want the nationalist to be made out as heroes, the black nationalists wanted to forget about it because it was African Americans attacking police. If you come to Cleveland like I did, from outside the city, you hear about the Hough riots two years earlier, but there was twice the destruction in Glenville and nobody talks about it because of this legacy that it has.

The most important thing is to understand what happened and talk about it, reveal it and deal with the trauma that is attached to it. Because it has not gotten better, it’s gotten worse. There’s a lot of destruction still going on. Step number one is to stand up and say, “We’re racist, we have a racist past, and we have to deal with it,” and step two is to say, “Look at 1968. We were on the right path. You had this idea of investing vast amounts of money in solving the problem, and we need to get back to that.”

Your appearance at the library is the day after Election Day. In light of the upcoming midterms, what do you hope readers will take away from the book?

With the election of Donald Trump, it’s completely obvious to everybody, even his supporters, that we have fallen back into racist politicians using race to juice their base. We saw it in Charlottesville, we continue to see it. It’s our national disgrace. People need to get out and vote because right now there’s no check on it. We’ve seen in the last two years that these things begin to build their own momentum. Just today, we’re seeing somebody sending explosives to President Obama, Hillary Clinton, CNN—this can become a really dangerous situation if what’s going on in the presidency is not checked. People need to vote. Otherwise we will continue down a path that is more and more destructive.

I am so glad that our book club is reading “Ballots and Bullets,” due to the fact that I am learning valuable history. I have never thought about these issues in a deep way as a white, lifelong Clevelander. It has awakened in me an interest and concern about racial injustice, and I will never be complacent again.